Operative procurement is the engine of day-to-day purchasing in any organization. It deals with converting purchase requests into orders, getting goods and services delivered on time, and ensuring payments are handled correctly. In this introduction, we use Arjan van Weele’s procurement model as a foundation to explain what operative procurement entails and we dive deeper in the Operative buyer role.

We’ll outline the operative buyer’s responsibilities in manufacturing, retail, and service environments, discuss how demand for purchases is triggered in different ways, and show how what you buy (direct materials, MRO supplies, or services) affects daily work and the systems used. Finally, we connect how operative buying supports tactical procurement activities like contract management, supplier performance, and spend visibility. The post is focused on practical insights for procurement trainees and an integrated part of the Learn How to Source basic level course Operative Procurement Processes.

Content…

Van Weele’s Procurement Model: Linking Tactical and Operative Purchasing

Arjan van Weele’s classic model breaks the procurement process into a series of steps, typically six key stages. These include defining the specification of needs, selecting suppliers, negotiating & contracting, ordering & expediting, and evaluation & follow-up. Broadly, the early steps (specification, supplier selection, contracting) are often considered tactical procurement – they involve deciding what to buy, from whom, and under what terms. The later steps (ordering, expediting/delivery, and payment processes) fall under operative procurement – the execution of purchases based on those agreements. Importantly, Van Weele emphasizes that once contracts are in place, “the operational procurement process then takes place”, meaning operative buying works within the frameworks set by tactical procurement. Learn more about Tactical Procurement

Arjan van Weele’s procurement process separates tactical purchasing (upstream activities like specifying needs and contracting suppliers) from operative purchasing (downstream activities like ordering, expediting, and payment). The operative procurement cycle – often called purchase-to-pay (P2P)– begins with an internal need and ends with the supplier’s delivery and invoice being settled, all under the guidance of established contracts and supplier relationships.xentys.nl

In practice, operative procurement (the right-hand side of Van Weele’s model) starts when an internal internal customer or department signals a need. This could be via a formal purchase requisition, an automated trigger in an ERP system, or another demand signal. The operative buyer’s role is to convert that need into a purchase order (PO), ensure it’s properly authorized, and then work with the supplier to receive the goods or services as agreed xentys.nl.

They then complete the process by matching the supplier’s invoice to the order and the receipt (the classic 3-way match) to authorize payment. All of this happens in alignment with the contract terms (price, delivery, quality, etc.) that were negotiated by tactical procurement. If a needed item or service has no contract in place, an operative buyer may need to perform a quick spot-buy by seeking quotes and negotiating on a smaller scale – but usually only if the purchase value is below a certain threshold of authority. This ensures that operative procurement stays efficient and compliant, leveraging agreements that cover the vast majority of spend.

Before diving into specific industries, it’s worth noting why operative procurement is so critical: depending on the industry, procurement expenditures represent a huge share of company revenue – around 20% in services, 60% in manufacturing, and up to 95% in retail xentys.nl. This means operative buyers managing the flow of orders and deliveries are directly handling a large portion of the company’s costs and operational needs. Now, let’s explore what operative buyers do in different business environments.

Operative Buyer Responsibilities in Manufacturing

In a manufacturing environment, operative procurement is tightly integrated with production planning. The operative buyer’s primary mission is to ensure that materials and components arrive on time to keep production lines running smoothly, at the right quality and optimal cost. Key responsibilities of an operative buyer in manufacturing include:

- Translating production needs into orders: Manufacturing companies often use Material Requirements Planning (MRP) systems to calculate what raw materials or parts are needed and when. The operative buyer reviews planned orders from MRP (which are based on production schedules, forecasts, and current inventory) and converts them into purchase orders to send to suppliers. For example, if an automotive plant’s MRP shows a need for 10,000 units of steel and 1,000 tires next month, the buyer will generate POs to the steel mill and tire supplier as per the agreed schedule.

- Supplier coordination and expediting: The buyer monitors open orders and works closely with suppliers to ensure on-time delivery. If a delivery is at risk of delay, the buyer expedites it – taking action only when exceptions arise (exception-based expediting) or sometimes proactively following up on every critical shipment. Keeping production fed often requires daily communication with suppliers and the internal production team.

- Inventory and order quantity optimization: Manufacturing operative buyers try to balance having enough stock to prevent line stoppages with minimizing excess inventory. They often order in economic batch sizes or on a just-in-time basis per contract terms. They must be familiar with agreed lead times, minimum order quantities, and other terms negotiated by tactical procurement.

- Quality and issue resolution: If raw materials arrive and fail quality checks, or if wrong quantities are delivered, the operative buyer manages the claims or returns process (complaints management). They coordinate with quality control and the supplier to get replacements or credit, ensuring production isn’t impacted.

- 3-way match and payment approval: After goods are received in the factory warehouse, the buyer (or accounts payable team) matches the supplier’s invoice against the PO and the receipt. Any discrepancies (price differences, missing items) are resolved. Only then is payment approved, closing the purchase loop.

Real-life example: Consider a pharmaceutical manufacturer. An operative buyer sees that a new batch of medicine is scheduled for production in 8 weeks, which will require a special chemical ingredient. Through the ERP system, a planned order is generated for that ingredient. The buyer converts it to a PO and sends it to the approved supplier under an existing contract. Because the ingredient has a long lead time, the buyer issues the order early. They then follow up weekly with the supplier to track progress. When the shipment is sent, the buyer coordinates with the warehouse for urgent receipt since production is waiting. Upon delivery, they verify the delivery note and quality reports, then approve the invoice for payment – all in alignment with the contract pricing and terms that were pre-negotiated.

Manufacturing operative buyers rely heavily on ERP and MRP systems to trigger orders and track status. Tools like SAP, Oracle, or other manufacturing ERPs help automate a lot of this process. For instance, an MRP run can automatically suggest procurement actions by analyzing forecasts, open orders, inventory levels, and supplier lead times. Many manufacturing firms also integrate supplier portals or EDI (Electronic Data Interchange) with key suppliers – this allows, for example, a car manufacturer’s system to automatically send order schedules to a tire supplier and receive confirmations or advance shipment notices electronically. The result is a tightly coupled process where operative buyers focus on managing exceptions (like expediting a late delivery or resolving a quality issue) rather than manually placing every routine order.

Operative Buyer Responsibilities in Retail

In a retail environment, operative procurement is about keeping the shelves stocked (whether physical or virtual shelves) with the right products. Retail operative buyers (often called retail buyers or replenishment analysts) handle a vast array of SKUs and must respond quickly to sales trends. Their responsibilities include:

- Replenishment and stock level management: Retailers use automatic replenishment systems that monitor store or warehouse inventory in real time and trigger reorders when stock falls below a set reorder point inciflo.com. The operative buyer sets or adjusts these reorder points and parameters based on desired service levels. For instance, a supermarket buyer might set a high-priority item like milk to reorder when stock gets down to 2 days of sales to maintain a 98% service level (item availability for customers). Modern systems can automatically create POs when thresholds hit, which the buyer then reviews and approves.

- Manual ordering for promotions or new products: Not all retail purchasing is automatic. If there’s an upcoming promotion or seasonal peak (e.g. ordering extra chocolate before the holidays or new summer clothing lines), the buyer manually forecasts demand and places bulk orders in advance. They work with merchandising and sales departments to anticipate needs. In this way, operative buyers in retail also manage forecast-based orders to ensure sufficient inventory for expected spikes.

- Supplier liaison and delivery scheduling: Retail buyers coordinate with suppliers (which may be manufacturers, wholesalers, or distributors) to arrange deliveries into distribution centers or stores. They must consider lead times and often use just-in-time deliveries to avoid overstock. For example, a fashion retail buyer might arrange with a supplier to deliver new collections in multiple smaller batches timed with store resets, rather than one large delivery, to keep inventory fresh and lean.

- Inventory accuracy and service level monitoring: Retail procurement is highly metrics-driven. Buyers keep an eye on stockouts (when something sells out) and overstocks. They use KPIs like fill rate or service level – if the desired service level is 95% on a certain item, the system might trigger replenishment earlier to avoid dropping below that availability. The operative buyer adjusts parameters or expedites orders to hit these targets. They also manage allocations (deciding how to distribute limited stock across stores) when supply is constrained.

- Pricing and catalog updates: In some retail organizations, buyers also handle the administrative side of ensuring the correct purchase prices are on POs (especially if there are frequent promotions or deals from suppliers). They maintain the procurement catalog or system data for items so that orders reflect current terms. This ensures that invoice matching is smooth – since any price discrepancy between order and invoice will need resolving.

Real-life example: Imagine a home electronics retailer. Their system shows that a popular gaming console is selling faster than expected this week. The automatic system flags that inventory will fall below the safety stock in 3 days and triggers a reorder to the supplier for 500 more units. The operative buyer quickly reviews this order, checks it against the upcoming marketing events (perhaps a sale was announced increasing demand), and approves it.

They then call the supplier to ensure those consoles can ship immediately. Meanwhile, they’re also preparing a forecast order for an upcoming holiday season – projecting how many TVs and tablets to buy in advance, since suppliers might need a long lead time to fulfill those. When the consoles arrive at the distribution center, the buyer confirms receipt in the system and verifies the invoice matches the agreed unit price and quantity. By balancing automated triggers with human oversight and planning, the retail operative buyer keeps product availability high and customers happy, while controlling inventory costs.

Retail operative buyers often make use of specialized inventory management software or modules within ERPs that handle high-volume, repetitive ordering. Automated replenishment is common: for example, e-commerce giants like Amazon have systems to ensure high-demand products are reordered automatically when stock falls below a threshold inciflo.com. The buyer’s role is to supervise these systems, adjust for factors the algorithms might not know (like upcoming ad campaigns), and manage exceptions (delays, stock shortages, etc.). Retailers may also use vendor-managed inventory (VMI) arrangements for some products, where the supplier is responsible for monitoring the retailer’s stock and triggering refills – but even in VMI, an operative buyer coordinates the relationship and ensures the supplier adheres to agreed service levels.

Operative Buyer Responsibilities in Service Organizations

In a services environment (like a bank, a software company, a hospital, or any non-manufacturing, non-retail business), operative procurement focuses largely on indirect purchases – the goods and especially services that enable the business to run. These can range from office supplies and IT equipment to outsourced services like facility management, consulting, or temporary labor. The operative buyer’s responsibilities in a service organization typically include:

- Processing internal service requests and purchase requisitions: Unlike manufacturing or retail, demand in service industries is often driven by manual requisitions from internal users. For example, an HR department might raise a requisition for a training workshop service, or the IT team might request new laptops. The operative buyer reviews these requests for completeness and compliance (correct descriptions, budget codes, etc.) and then converts them to POs once approved xentys.nl. They ensure each purchase is necessary and falls under any existing contract or budget limits.

- Calling off services against contracts: Service companies often have many ongoing service contracts (e.g. cleaning services, maintenance contracts, IT support agreements). The operative buyer creates release orders or schedule orders as needed under these contracts. For instance, if there’s a contract for legal consulting services up to a certain number of hours, the buyer might issue a PO for a specific engagement referencing that contract. They must understand the contract terms and scope to issue orders correctly (e.g. knowing the agreed hourly rate and not exceeding the contracted hours without approval).

- Ensuring service delivery and quality: Because services are intangible, operative procurement must often verify that the service was delivered to satisfaction before approving payment. This could involve obtaining confirmation from the end user that a service was completed successfully. For example, after a consulting project is done, the buyer might require a sign-off from the department that the deliverables were received. In a facilities context, if a repair service was performed, the buyer ensures the issue is resolved. This is a quality control aspect, analogous to checking goods for quality – but here it’s about service performance.

- Managing suppliers and contractors: Operative buyers in services maintain communication with service providers for scheduling, issue resolution, and relationship management. They may handle contract renewals administratively by reminding the tactical or contracting team when a service contract is nearing its end date and gathering any needed information to extend or rebid it. They also track KPIs like vendor response times or fulfillment of service level agreements (SLAs). If a supplier isn’t meeting performance expectations (e.g. a cleaning service consistently missing areas), the operative buyer will address it with the supplier, or escalate it for tactical procurement to intervene or consider alternative vendors.

- Routine indirect purchasing and catalog management: Service organizations still need MRO supplies and consumables (from office stationery to spare parts for facilities)(MRO). Operative buyers often maintain catalogs or online procurement portals for employees to order standard items (like via an e-procurement system). They ensure these catalogs are up to date with correct suppliers and pricing. When employees select items from a catalog (say, ordering a new office chair from an approved list), it generates a requisition that the buyer can quickly convert to a PO since the item, price, and supplier are pre-approved. This streamlines low-value purchasing and frees up time to focus on larger service procurements.

Real-life example: Consider a large hospital (service sector). An operative procurement officer receives a request from the cardiology department for an external medical equipment maintenance service – a vital machine needs servicing by an authorized vendor. The hospital has a contract with a maintenance provider, so the buyer creates a purchase order referencing that contract and schedules the service visit. They ensure the PO includes the agreed hourly rate and notifies the provider. Separately, the hospital’s facilities team needs to order cleaning supplies and some HVAC filters.

The buyer uses an e-procurement catalog to order these MRO items from a contracted janitorial supplier. Later, when the maintenance service is done, the cardiology department confirms the machine is back in operation. The buyer then approves the service provider’s invoice for the hours worked, cross-checking that it aligns with the contract terms. In this scenario, the operative buyer juggles both service procurement (coordinating and confirming an intangible service) and indirect goods purchasing, ensuring all follow the hospital’s contracts and standards.

In service organizations, intangible services can be harder to specify and measure compared to physical goods. The operative buyer must often focus on the provider’s reliability and the outcomes delivered rather than technical specs. Long-term relationships are common – e.g. an IT services firm might stick with a trusted subcontractor for years – so operative procurement involves nurturing these relationships and ensuring mutual expectations are met. System support in this environment often includes e-Procurement tools and contract management systems. For example, a company might use a procurement portal where employees can request services or choose from pre-negotiated service catalogs (like a list of approved training vendors).

The operative buyer uses the system to route requests for approval and then issue POs. Supplier portals may be used here too for services – a consulting firm might submit their time sheets or deliverables through a portal for the buyer to review. While ERP systems (like Oracle or SAP) are still used to issue POs and do invoice matching, these are often augmented with modules specifically for services procurement (handling things like milestone payments or service entry sheets to confirm work done).

How Demand is Triggered: From Requisitions to Automatic Reorders

Operative procurement doesn’t happen in a vacuum – it responds to triggers that signal a need to buy something. Understanding these triggers is crucial for an operative buyer, as it determines how proactive or reactive their work is. Here are different ways demand is triggered, with examples:

- Manual Purchase Requisitions: This is a common starting point for many purchases, especially in service organizations or for non-routine needs. A purchase requisition is an internal document or request that an employee or department creates to ask the procurement team to buy something. It typically includes a description of the need, quantity, desired timing, and often a suggested supplier or budget code tipalti.com. For instance, a marketing manager might submit a requisition for a venue rental for an event. Once this requisition is approved internally, the operative buyer turns it into a PO and proceeds with the purchase. Manual requisitions ensure that all purchases are reviewed and necessary – the step acts as a checkpoint before any external order is placed. Operative buyers often manage a queue of requisitions in an e-procurement system, checking each for completeness and proper approval signatures.

- Automatic Reorder Point Triggers: In inventory-based businesses (manufacturing and retail primarily), many orders are triggered not by a person but by the inventory system. A reorder point (ROP) is a preset stock level that signals when it’s time to reorder. For example, if a warehouse has a reorder point of 100 units for a certain component and the stock falls to 100 or below, the system will flag the need to replenish. Modern systems can automatically generate a PO or at least a requisition when this happens inciflo.com. As a real example, a retail store might set a reorder point of 5 units for a fast-selling product; when the shelf stock drops to 5, the system auto-creates a replenishment order from the central warehouse. The operative buyer’s job is largely to oversee these auto-triggers – making sure the parameters (like reorder points, safety stock, and order quantities) are set correctly to balance availability vs. carrying cost. Automated triggers greatly reduce the manual workload and help avoid stockouts by “ensuring that stock levels are optimized in real-time”, but they require the buyer to maintain data and respond to any anomalies (like if the system suggests an unusually large order, the buyer should investigate why).

- Planned Orders from MRP and Forecasts: In manufacturing (and some large-scale retail operations), MRP (Material Requirements Planning) is a core engine for triggering purchase orders. MRP looks at production plans or sales forecasts, existing inventory, and lead times to automatically calculate what needs to be purchased or produced, and when. The output of MRP for procurement is a set of planned orders – basically recommendations to buy certain quantities by certain dates. These are a form of system-generated requisition. The operative buyer reviews planned orders and converts them to actual POs. For example, in a furniture manufacturing company, if the MRP run shows a planned order for 500 wooden panels needed in 4 weeks (because a big batch of tables is scheduled), the buyer will turn that into a purchase order to the wood supplier. Forecast-driven triggers are similar: if a company forecasts higher demand next quarter, they might schedule purchases in advance. Operative buyers often collaborate with demand planning teams to adjust orders based on the latest forecast (e.g., increasing orders for components that are predicted to sell more). Essentially, MRP and forecasting create a proactive trigger so that procurement is done ahead of need, rather than reacting at the last minute. This automation is a huge efficiency gain – one source notes that an MRP system “automates procurement and scheduling decisions” by crunching numbers that would be impossible to handle manually. Buyers, however, must validate these suggestions and handle any vendor communications or changes required. Learn More about Demand management in Learn How to Source free online course.

- Service-Level or SLA Triggers: Some procurement activities are triggered by service level considerations. For inventory, this can overlap with reorder points and safety stock – for instance, maintaining a high service level (product availability percentage) might mean triggering a replenishment earlier or ordering extra safety stock. In a maintenance context, a service-level agreement (SLA) might trigger procurement too. For example, if an SLA requires that a machine must have 99% uptime, the operative buyer might need to ensure critical spare parts are always on hand above a threshold (auto-replenished when one is used) or that a backup service provider is called in if the primary fails to respond in time. Another example: in IT services procurement, if a support vendor is not meeting the SLA (e.g., not resolving issues within 4 hours as promised), it might trigger a review or bringing in additional support – essentially a need to procure more resources or escalate to another supplier. Service-level triggers are about maintaining performance standards, and when those standards are at risk, they prompt procurement action. While these triggers are often embedded in contract management or performance monitoring tools rather than inventory systems, they are an important part of operative procurement in services – the buyer must keep an eye on KPI dashboards and be ready to procure solutions (like emergency spare parts, or contracting an alternate service provider) when needed to uphold service levels.

In summary, demand can be signaled either by people (internal requisitions, management decisions based on forecasts) or by systems (auto reorder points, MRP calculations, SLA monitors). A skilled operative buyer knows how to work with all these triggers – setting up systems to automate what can be automated, and handling human-initiated requests efficiently. This ensures no legitimate need goes unfulfilled and resources are used wisely.

Direct Materials vs. MRO vs. Services: How Purchase Category Shapes the Process

Not all purchases are created equal. The day-to-day work of an operative buyer can look very different depending on whatthey are buying. Generally, we can classify purchases into direct materials, MRO/indirect supplies, and services. Each category has its nuances and often uses different system supports:

- Direct Materials (Production Inputs): These are the raw materials, components, or products that directly go into a company’s end product or resale inventory. In manufacturing and retail, direct materials are the lifeblood of the business – e.g. sheet metal for an appliance maker, or finished goods that a retailer sells in stores. Because direct materials impact the final product and customer directly, they tend to involve bigger budgets and more structured processes. Operative buying of direct materials is usually highly systematized: companies utilize ERP systems with MRP modules to manage this. The goal is to ensure a reliable supply of inputs without interruption. As noted earlier, MRP and e-procurement tools are leveraged to manage direct procurement, along with analytics to track spend and supplier performance sap.com. Operative buyers for direct materials often work closely with tactical buyers who negotiated contracts for those materials. Daily work includes release orders against long-term contracts or schedules (sometimes called call-off orders or schedule agreements), managing just-in-time deliveries, and monitoring quality issues because any defect can affect production. System support is deeply integrated – for example, automotive companies might use EDI or supplier collaboration platforms to automatically send weekly or daily order releases to suppliers for direct materials. Any hiccup in direct material supply can halt production or leave store shelves empty, so operative buyers in this area are very focused on precision and timeliness. They also engage in spend analysis tools built into ERPs to track material costs vs. budgets, helping the tactical team identify when to renegotiate prices if, say, commodity prices drop.

- MRO (Maintenance, Repair, and Operations) and Indirect Supplies: MRO items are supplies that keep the business running but do not end up in the final product. This can include spare parts for machines, tools, safety equipment, office supplies, cleaning materials, etc. MRO purchases are often numerous but of lower individual value. The operative buyer’s challenge here is managing a broad range of items and suppliers efficiently. Many organizations implement catalog management and e-procurement portals for MRO: they pre-negotiate catalogs of frequently used items (like a catalog for office supplies or factory spare parts) so that internal users can directly order against those. The operative buyer maintains these catalogs, perhaps updates pricing periodically, and processes orders in bulk. System support for MRO is typically an e-Procurement tool or module that simplifies requisitioning and approvals – some companies give end-users access to shop from catalogs, then the buyer just oversees the consolidated orders. MRO buyers also pay attention to inventory levels for critical spares. For example, they might keep a small inventory of replacement parts for key machinery and set automatic reorder points similar to direct materials. One key difference is that MRO procurement is often about responsiveness – if a machine breaks down, the buyer might need to rush order a part or service to fix it, since downtime is costly. The role of an MRO buyer is thus critical to minimize downtime and avoid disruptions. They act as the go-to person to quickly source whatever is needed to keep operations running (hence why MRO buyers are sometimes called the “unsung heroes” ensuring everything runs like a well-oiled machine). This can involve maintaining relationships with many small suppliers and possibly using p-cards (procurement credit cards) or spot buying for urgent needs that aren’t in the catalog. While each MRO purchase might seem minor, collectively they have a significant impact on cost and efficiency. Good MRO operative buyers implement cost control by finding cheaper alternatives or optimizing stock levels without compromising operational readiness. Modern systems and procurement automation software can assist by aggregating MRO spend, automating approvals for low-value purchases, and alerting buyers when spending patterns change (indicating, for example, a certain part is being consumed faster than before, which might warrant a tactical review).

- Services Procurement: Procuring services (consulting, marketing agencies, facility management, IT services, etc.) is quite different from buying goods. The “specification” of a service is often a statement of work or performance outcome rather than a physical description. Operative buyers handling services rely heavily on contracts – because services typically need a contract outlining scope, deliverables, timelines, and rates. The daily work for services procurement involves coordinating service delivery (ensuring the service provider and internal requester are on the same page for scheduling and expectations) and then verifying completion. Systems that support service procurement might include contract management systems to track contract terms and renewals, and features in ERP or procurement software to record services delivered (for instance, in SAP there are Service Entry Sheets that an operative buyer or the end user can fill out to confirm a service was performed, which then allows the invoice to be paid). Supplier portals can be useful here too: a contractor might log their hours or task completion in the portal, which the internal team then approves. One key aspect is measuring quality and compliance for services – since you can’t “inspect” a service like a product, companies use KPIs and feedback. Operative buyers might send satisfaction surveys to internal stakeholders after a service is rendered or track if the service met the SLA. The nature of services also means operative buyers may deal with variation in scope – a project might expand or contract, requiring change orders. Thus, flexibility and communication are vital skills. From a system perspective, spend visibility on services is often less transparent than for goods (because service specs may vary), so operative buyers ensure that each service PO is linked to a project or category for analysis. For example, they might tag all training-related service POs so later the company can see total training spend. As noted in industry analyses, procurement of services often involves longer-term relationships and more customization. This means an operative buyer for services might be continuously involved with the same provider (e.g. an IT support vendor), issuing POs each month or quarter and managing that ongoing relationship, rather than one-off transactions. Tools that integrate procurement with vendor management (especially for categories like temporary labor, where a Vendor Management System (VMS) might be used) are common in services procurement.

In practice, operative buyers often handle all three categories to some extent, but many organizations split roles: one team may focus on direct materials, another on indirect/MRO, and another on services. Each requires a slightly different approach and toolset, but all share the core P2P process discipline. The best operative buyers understand the business impact of each category – for example, a delay in a direct material delivery could stop production, a lack of MRO supplies could cause maintenance delays, and a poorly managed service contract could lead to operational inefficiencies or legal issues. Therefore, they tailor their focus accordingly: perhaps more stringent follow-up for direct materials, more catalog streamlining for MRO, and more detailed scope verification for services.

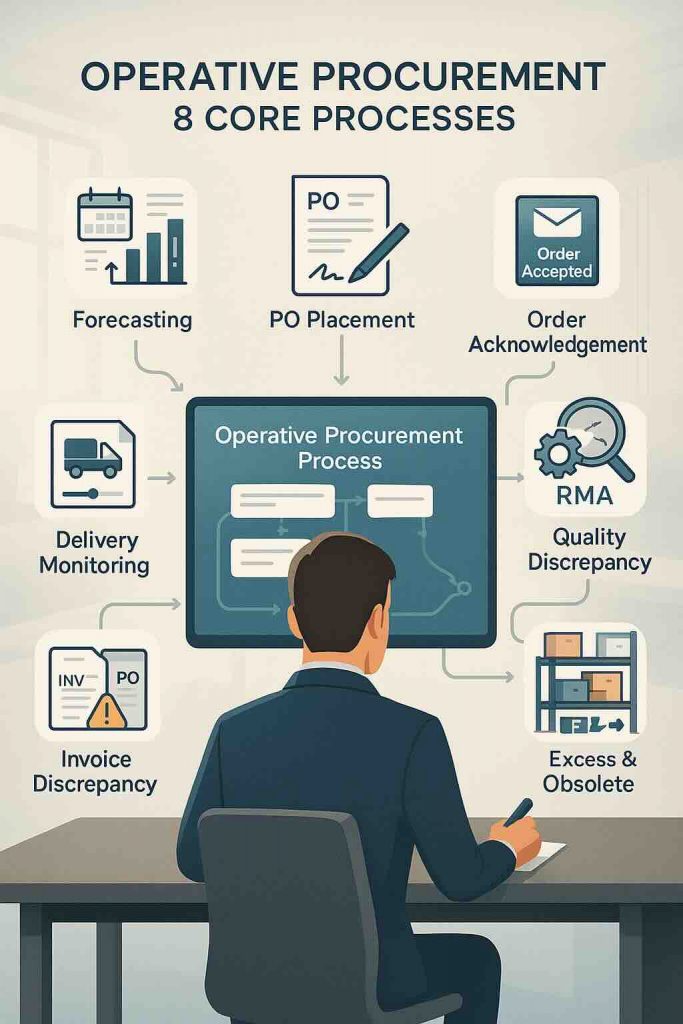

The Eight Core Processes of Operative Procurement

While every organization will have its own variation, most operative-buyer roles revolve around a common set of eight processes. These map directly to the purchase-to-pay cycle we described earlier, and each one depends on clear handoffs from tactical procurement (contracts, approved suppliers, pricing) as well as robust system support (ERP, e-procurement, supplier portals).

- Forecasting

Operative buyers take inputs from production plans, sales forecasts or historical usage and turn them into a clear “net forecast” per item and supplier. In manufacturing, this means running MRP to calculate what materials are needed when. In retail, you may translate seasonal sales projections into a replenishment forecast. And in services, you might produce a headcount or usage forecast for contingent labor or cloud-service consumption. The goal is always the same: give suppliers visibility so they can plan capacity and meet your delivery expectations. - Purchase-Order Placement

Once a forecast or requisition is approved, the operative buyer creates a formal purchase order (PO) in the ERP or e-procurement system. This step embeds the negotiated contract terms—unit price, payment terms, incoterms—into every order. By using the system to generate POs rather than emailing ad-hoc requests, you ensure accuracy, compliance and a complete audit trail. - Order Acknowledgement

A PO is only as good as the supplier’s confirmation. Operative buyers monitor acknowledgements—either via EDI, supplier portal, or simple email—to verify that the supplier has accepted the order exactly as requested. Any discrepancy in quantity, price, or delivery date must be addressed immediately to prevent confusion and downstream delays. - PO Management (Order Changes)

Business conditions can shift overnight. If demand falls, you may need to cancel or reduce a PO; if urgency spikes, you might request an early delivery or quantity increase. Managing these changes—issuing change orders, reconciling them in the system, and updating expected delivery dates—is a core daily task. Doing it electronically, and tracking approval workflows in your ERP, minimizes manual errors and keeps everyone aligned. - Delivery Monitoring

Even the best-run supply chain needs active oversight. Operative buyers review delivery schedules and lead-time commitments in the system, drill into exceptions when shipments are late, and work with logistics to expedite or reroute as needed. Many teams use simple dashboards or alerts that flag shipments approaching their promised delivery dates, so they can intervene only when necessary. - Quality Discrepancy Handling

When goods arrive, quality inspection may find defects or damage. The operative buyer coordinates the corrective process: logging a non-conformance, requesting a Return Material Authorization (RMA), arranging collection or replacement shipments, and updating the supplier’s performance record. Quick, consistent handling of these deviations protects production or stores from contaminated or unusable stock. - Invoice Discrepancy Resolution

The classic “three-way match” (PO, goods receipt, supplier invoice) lives here. Operative buyers compare invoices line-by-line against the order and the receipt. Price, quantity or tax discrepancies trigger investigations. Is the price wrong because the contract was updated? Did the supplier over-ship? Resolving these variances promptly—either via a credit memo or a supplier discussion—avoids late-payment penalties and ensures accounting accuracy. - Excess & Obsolete (E&O) Management

Despite your best forecasts, some materials or parts fall out of use. Operative buyers help define what constitutes excess (e.g. fewer than X months of projected demand) or obsolete (zero forecast). They then collaborate with stakeholders to find secondary buyers, return goods to the supplier, or arrange for scrap. Proactive E&O management frees up working capital and warehouse space—and informs future forecast and ordering policies.

Each of these eight processes reflects the operative buyer’s daily rhythm: interpreting demand signals, executing orders against tactical contracts, resolving issues that threaten continuity, and feeding back performance data and lessons learned into the next sourcing cycle.

How Operative Procurement Supports Tactical Procurement

Operative buyers are on the front lines of the procurement function, but they don’t work in isolation. Their activities are closely connected to tactical procurement (the sourcing and contracting side). Here’s how operative procurement supports and interfaces with tactical procurement activities:

- Executing Contracts and Ensuring Compliance: Once tactical procurement (or a strategic sourcing team) has negotiated a contract with a supplier, it’s the operative buyer’s job to execute purchases according to that contract. This means they use the contracted supplier and pricing for all relevant orders, they reference contract terms in POs, and they adhere to the agreed processes (like ordering lead times or using a specific ordering platform if required by the contract). By doing so, operative buyers ensure the organization actually realizes the benefits that were negotiated (volume discounts, service level guarantees, etc.). They need to be very familiar with the contracts and terms & conditions that apply. For example, if a contract states that free shipping applies for orders over a certain volume, the operative buyer should try to batch orders to meet that if possible. Compliance also means preventing maverick spending – if someone tries to buy from an unapproved supplier when there is already a contract in place, the operative buyer will redirect the purchase to the contracted source. In this way, operative procurement enforces the preferred supplier and contract strategies set by tactical procurement.

- Supplier Performance Feedback and Follow-up: Operative buyers interact with suppliers every day – sending orders, chasing deliveries, resolving invoicing issues. They are often the first to know if a supplier has a problem (late shipment, quality issue, communication gap). All this information is critical for supplier management, which is usually a tactical procurement responsibility. Operative procurement provides the eyes and ears on supplier performance. They might keep records of on-time delivery rates or issue logs and regularly share these with the tactical team or category manager. If minor issues occur, operative buyers handle them directly with the supplier (e.g. arranging a rush shipment or sorting out a pricing discrepancy). If issues become chronic or significant, the operative buyer will escalate to tactical procurement for supplier review or renegotiation discussions. For instance, if a supplier has delivered late three times in a month, the operative buyer might involve the tactical buyer to discuss corrective action or consider alternate suppliers. Thus, operative procurement’s diligence in monitoring and communicating supplier performance supports tactical procurement’s role in maintaining and improving supplier relationships.

- Spend Visibility and Data for Decision Making: Every purchase order an operative buyer places and every invoice they process generates data – data about what was bought, in what quantity, from which supplier, at what price, and for which internal purpose. This data is gold for tactical procurement and higher-level procurement strategy (Spend analysis course). Operative procurement ensures that data is accurately captured and categorized. For example, the operative buyer will make sure to select the correct category or commodity code when creating a PO (office supplies vs. IT equipment vs. marketing services, etc.), and tag the correct project or cost center. They also might consolidate purchases to the same supplier when possible, which makes spend patterns clearer. All this feeds into spend analytics that tactical procurement uses to identify opportunities. For instance, if operative purchasing data shows that multiple departments are buying a certain software license separately, the tactical team can initiate a bulk negotiation. Moreover, by following the P2P process properly (requisition → PO → goods receipt → invoice), operative procurement helps maintain a clear audit trail. This ensures the company knows where its money is going – a prerequisite for any spend visibility initiative.

- Supporting Tactical Initiatives: Operative buyers often participate in or enable tactical procurement projects. One example is during a new contract implementation – after tactical procurement signs a deal with a new supplier, operative procurement might help load the new supplier and items into the system, educate end-users about the new process (for instance, “we have a new office supplies catalog starting next month – please order from Supplier X’s catalog instead of the old one”), and perhaps run initial orders to test the arrangement. Another example is product or supplier phase-outs: if a certain material is being phased out or a supplier is being replaced (due to a tactical decision), the operative buyer manages the transition – planning final orders from the old supplier, running down inventory, and smoothly switching to the new source without interrupting operations. Operative procurement can also provide insights during sourcing: tactical teams might ask them, “what issues have you faced with the current supplier?” or “do you think we can manage with a longer lead time if it means a cheaper source?”. The operative buyer’s on-the-ground experience is invaluable in shaping practical sourcing requirements and ensuring that new contracts are realistic to execute.

- Handling Non-Contracted Purchases within Policy: Tactical procurement can’t feasibly have contracts for every single thing an organization buys. There will always be some non-contracted or one-off purchases. Operative procurement steps up to handle these within defined policies. Many companies give operative buyers a certain authorization limit for spot buys xentys.nl. For example, if a needed item costs less than say $5,000 and there’s no contract, the operative buyer can quickly find a supplier, get a few quotes (to ensure a fair price), choose the best option, and make the purchase – all while following procurement guidelines. This ability to conduct mini-tenders or small negotiations means the company can be agile and not bog down the tactical team for trivial purchases. However, operative procurement will still document these and often later inform tactical procurement. If many such spot buys of a similar nature occur, it flags to tactical procurement that perhaps a contract or strategic sourcing effort is needed for that category. In essence, operative buying acts as a safety net to meet immediate needs without undermining strategic agreements. By keeping tactical informed and adhering to policy (like getting competitive bids or using preferred vendors where possible), they support the larger strategy and sometimes even highlight new opportunities for strategic sourcing.

In summary, operative procurement is closely intertwined with tactical procurement. One can think of tactical procurement as designing the playbook (choosing suppliers, setting terms, establishing policies) and operative procurement as executing the plays on the field. A feedback loop exists: operative buyers execute and provide real-world results (on supplier performance, actual spend, user behavior), and tactical buyers adjust the strategy based on that.

Both roles together form a cohesive procurement function. A well-run procurement organization ensures that operative and tactical teams communicate frequently and understand each other’s needs and constraints. For instance, operative buyers should be aware of the strategic importance of certain suppliers or contracts, and tactical buyers should understand the practical challenges operative teams face with lead times or system tools.

Conclusion

For a procurement trainee, mastering the operative procurement function is a fundamental step. It’s where procurement strategy meets reality – every day, operative buyers keep the business supplied and running. Using Van Weele’s model, we see that operative procurement covers everything from the moment an internal need is identified to the final payment of the supplier’s invoice. In this journey, an operative buyer in a manufacturing firm will be deeply involved in production material flows and MRP schedules, in retail they’ll focus on stock replenishment and reacting to consumer demand, and in services they’ll juggle contracts and intangible deliverables.

Demand triggers can be manual or automated, and knowing how to manage both is key to staying efficient and responsive. The nature of what is procured – be it direct production materials, MRO supplies, or services – introduces specific challenges and tools, from ERP systems and catalogs to supplier portals and contract management platforms.

Always remember that operative procurement doesn’t work in isolation: it is part of a larger procurement ecosystem. By diligently executing orders and managing supplier interactions, operative buyers reinforce the contracts and strategies developed by tactical procurement, and provide the groundwork for strategic decisions (through spend data and performance insights). For a trainee, developing skills in communication, organization, and familiarity with procurement systems (ERP, e-procurement, etc.) is just as important as understanding procurement theory. An operative buyer must be detail-oriented (to catch discrepancies), proactive (to prevent issues like stockouts or lapses in service), and collaborative (to work with internal stakeholders and suppliers effectively).

In essence, the operative procurement function is where “the rubber meets the road” in supply management. It’s a role that may not always be visible externally, but it is crucial to organizational success, ensuring that every contract and every plan actually delivers value through timely, cost-effective purchasing. By learning the ropes of operative procurement, buyers in training lay the foundation for a successful career in procurement – one where they can later drive tactical and strategic improvements with the confidence that comes from hands-on execution experience. With the knowledge of how each purchase is triggered and fulfilled, and how it ties back to bigger objectives, a procurement professional is well-equipped to contribute to their organization’s efficiency and competitive advantage.

Note: Illustration to Blogpost “Understanding the Operative Procurement Function (Van Weele’s Model in Practice)” was created by Sora on April 26, 2025.